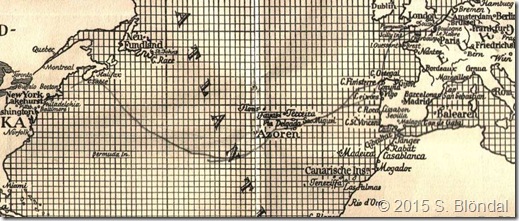

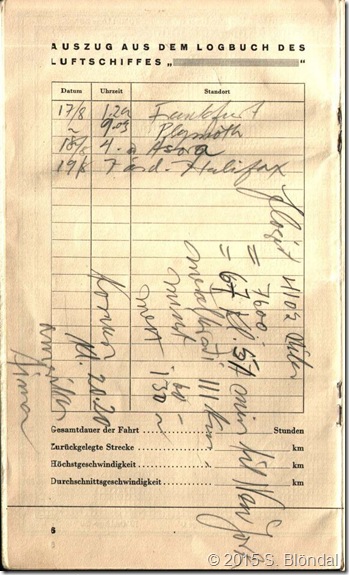

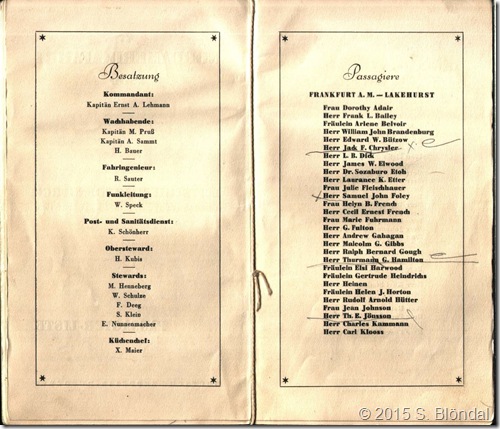

Last year, I received an email from a gentleman named Steen Blöndal, attached to which were scans of an official DZR passenger list that his grandfather, Thóroddur Jónsson, had saved as a souvenir from his flight to the United States aboard the Hindenburg on her 7th North American flight (August 17-19, 1936). In addition to the names of all of the passengers carried on that flight (along with a number of autographs from them), the list contained notes from Mr. Jónsson on the flight, listing distance traveled, air speed, landmarks passed, etc. There was even a printed map on which Mr. Mr. Jónsson had marked the Hindenburg’s flight path.

This piqued my interest, and I began to research this particular Hindenburg flight to see what else I could find out about it. As it turns out, there were a number of notable bits and pieces of information to be learned. So I thought that it might be interesting to try and chronicle this, one of the Hindenburg’s lesser-known flights.

Over the course of 34 flights since first being launched from her construction hangar on March 4th of that year, the Hindenburg had proven to be a solid, dependable airship. In addition to six round trip flights to and from the United States, the dirigible had been to South America and back three times; in March, only a few weeks after her first test flight, the new Zeppelin had made a four-day propaganda flight across Germany to promote Hitler’s demilitarization of the Rheinland; and in mid-June, the ship had made a special charter flight over Switzerland for VIPs from Germany’s steelmaking and arms manufacturing giant, Krupp AG. Furthermore, the Hindenburg had also made a number of day flights over Germany, carrying both VIPs and sightseers who could not afford the 1,000 Reichsmark ticket price (about $450 in US dollars) for a flight to the United States.

Now she was being provisioned for her latest voyage to the United States. Her transatlantic flights were quickly becoming routine—2 ½ days across the ocean, a sightseeing spin around New York City, and then on to her landing field at the Naval Air Station at Lakehurst, NJ. As no civilian airship port had yet been built in the United States, the Deutsche Zeppelin-Reederei, the corporate entity that handled arrangements for the Hindenburg’s flight operations, had contracted with the United States Navy to use the existing airship facilities at Lakehurst. Though the notion of a swastika-emblazoned German Zeppelin landing on a U.S. military reservation raised some eyebrows in the States, the US Navy had its own airship program and had determined that there was enough potential benefit to their own airshipmen to warrant extending the Germans provisional use of the Lakehurst air station. In early 1936, therefore, the DZR had been issued a revocable permit to land and reprovision the Hindenburg at the Lakehurst base, good only until the end of 1936. If the Hindenburg’s experimental first season of 10 round-trip flights went well and the political climate didn’t sour appreciably, the permit would be revisited for possible renewal for the 1937 season.

The Hindenburg had been scheduled for its standard 8:00 PM departure from Rhein-Main airfield, however a last-minute decision had been made to delay departure until midnight in order to await a shipment of newsreel films of the closing ceremonies of the Olympic Games, which had taken place earlier in the day. Ship’s commander Captain Ernst A. Lehmann conferred with his watch officers and the chief engineer about the four-hour delay, and it was determined that every effort would be made to ensure that the Hindenburg would sail from Lakehurst as close as possible to her scheduled departure time for her return flight, midnight on August 20th.

The Hindenburg’s fifty-eight passengers, assembled and waiting at the Frankfurter Hof hotel in Frankfurt, finally boarded the buses to the airfield at about 10:30 PM and arrived just before 11:30 PM. Upon arrival at Rhein-Main, passengers underwent a customs inspection, with customs officials making a particularly thorough search for German currency among the passengers belongings. Then, they were shown aboard the vast airship, stewards helping them up the embarkation gangway stairs that folded down from the ship’s belly and led to B-deck. From there, they climbed a second flight of stairs up to the airship’s main passenger areas on A-deck. Passenger cabins were arranged in the center of A-deck, with the dining salon on the port side and a lounge and reading room to starboard. Outboard of the dining room and the lounge, a promenade featuring broad, sloped mica observation windows ran the length of each side of A-deck.

Close friends and family members were allowed to gather in the hangar beneath the airship to wave their final “auf wiedersehens” to passengers who were now lining the ship’s observation windows. On boarding the airship, passengers were handed a special bound booklet containing information about the layout of the airship, onboard rules and regulations, a log and a map of the North Atlantic for passengers to track the flight, and also a list of their fellow passengers.

Thóroddur Jónsson was a 31 year-old merchant from Reykjavik, Iceland. Educated at Iceland’s Commercial College and then later in Vienna, In 1930, Jonsson had started an import/export business in 1930 and built a very successful and lucrative career as a wholesale trader. He mainly focused on Icelandic agricultural products, and did particularly well in the export of seafood and fur products. He would travel throughout Europe on business, and made a great many sales trips to Africa. Now, his business took him to the United States, where he would be staying at the Commodore Hotel in New York City. He then planned to return to Europe on August 26th aboard the Queen Mary, which would bookend his trip to America with a flight on the queen of the skies, and a sea voyage on the queen of the seas. Jónsson thumbed through the brochure that the stewards had handed him and looked over the passenger list to familiarize himself with the names of his fellow voyagers. As he would learn over the next couple of days, the roster of travelers on this flight ranged from captains of industry and merchants to engineers, military VIPs… and a taxidermist from Nebraska.

passenger list and the list of key members of the Hindenburg’s crew.

The taxidermist was 61 year-old James W. Elwood of Omaha. Born in 1875 and trained in taxidermy at a young age, Elwood developed his expertise not only through the business, but also through his love of sport hunting, which took him on hunting trips all over the world. He also passed on his knowledge of taxidermy to many of his friends and to a number of the world famous sportsmen he met in his travels. Eventually, in 1903, he opened the Northwestern School of Taxidermy, a correspondence school based in Omaha. His son, Rex, was currently vice-president and manager of the school, which would continue to sell taxidermy lessons by mail until it finally closed sometime around 1970.

James W. Elwood William J. Brandenburg

There were a number of other small businessmen aboard this flight, including William J. Brandenburg, also 61 years of age, who ran a successful engraving and electrotipping business in Los Angeles, CA. A colleague in the same industry, Carl Klooss was a 48 year-old metal manufacturer from Cincinnati, OH, where he ran the Enterprise Brass & Plating Company. Kloos, a native German from Hessen, had previously sailed to Europe in mid-May aboard the Hindenburg’s first eastbound flight from Lakehurst.

Harry Mather was the 52 year-old proprietor of Mather Brothers Furniture in Atlanta, a successful business that had grown to over a dozen stores throughout Georgia, South Carolina and Florida. Though he went by the name “Cotton” Mather, the Elkhart, IN native was not a descendent of the infamous Puritan leader of the same name, nor was he apparently any relation to Margaret Mather, who survived the Hindenburg’s fiery end the following May.

As usual, given the expense of the steep ticket price, many of the Hindenburg’s passengers were considerably more well-to-do members of the executive class. There was Jack F. Chrysler, the 24 year-old automotive scion, youngest son of Walter P. Chrysler, founder of the Chrysler corporation. 45 year-old Andrew Gahagan of New York was the president of a metal manufacturing corporation, while Tennessee-born Malcom G. Gibbs, age 48 and now living in Washington, DC, was the president of a chain of drugstores.

Andrew Gahagan Malcom Gibbs Samuel Foley

Perhaps more well-known to the news junkies of the day was Samuel J. Foley, District Attorney for Bronx County, New York. The portly, bespectacled 51 year-old Foley had made headlines for himself during the previous couple of years as he helped to build the case against Bruno Hauptmann for the infamous Lindbergh baby kidnapping.

hull. In preparation for loading, a panel of the airship’s outer cover has been

unlaced and hauled in, and the airplane’s wings have been removed.

(photo courtesy of the Luftschiffbau Zeppelin GmBH Archive)

(photo courtesy of the Luftschiffbau Zeppelin GmBH Archive)

Meanwhile, as the Hindenburg’s crew worked to ready the airship for takeoff in her hangar at Rhein-Main, they were joined by several military observers, who would be aboard the flight to make notes about the specific operational procedures used aboard the new airship. This had become common practice during the 1936 season, particularly on overseas flights where the Hindenburg’s innovative long-range navigational techniques came into play.

The United States, however, had no less than four official observers aboard the Hindenburg’s 7th flight to Lakehurst. As a condition of the revocable permit allowing the Hindenburg to moor at the Lakehurst Naval Air Station, the Navy had arranged with the DZR to send one or more senior airshipmen along on each of the airship’s transatlantic flights between Germany and the United States. The naval observers had free roam of the Hindenburg, and had in-depth conversations with the crew about the design and operation of the airship. Although the US Navy did not currently have any operational rigid airships (the sole Navy rigid, the German-made USS Los Angeles, was over a decade old and now relegated to the status of “hangar queen,” not having flown since 1932) they wanted to make sure to keep up to date on the latest developments in German technology in the event that approval was one day handed down for new naval rigid airships.

As head of the Bureau’s Lighter-Than-Air Design section, Fulton—known to friends and close colleagues by the nickname “Froggy”—was one of the Navy’s most qualified officers to observe and assess the design and operation of the Hindenburg, which was the world’s most advanced rigid airship. He had first been sent to Germany in 1922 as part of the team tasked with negotiating the purchase of what was then known merely as the “reparations airship”. The LZ 126 was custom-built for the US Navy by Luftschiffbau Zeppelin as a replacement for several German rigid airships that had been scuttled by their crews before they could be awarded to the United States under the conditions of the Versailles Treaty. Fulton remained in Germany at the Zeppelin works throughout the LZ 126’s construction and test flights, returning to the United States and his position at the Navy’s Bureau of Aeronautics once the airship had been delivered to the US and christened USS Los Angeles.

Fulton had flown aboard Germany’s next airship, the LZ 127 Graf Zeppelin, in 1933. Now, three years later, the Navy had arranged for him to fly to Germany aboard the Hindenburg’s August 9th eastbound flight along with Lt. Commander George H. Mills. Both men had toured the mooring facilities at Rhein-Main Airfield in Frankfurt as well as the Zeppelin works in Friedrichshafen before returning to the States aboard the August 17th flight.

Two months after returning from Germany, Mills was reassigned to Naval Air Station Sunnyvale in California, where he served as a tactical officer and navigator on the Navy’s last rigid airship, the USS Macon. Three months later, Mills was aboard the Macon when she crashed into the Pacific Ocean off of Point Sur, surviving the wreck along with all but two of the airship’s crew of 72 men. He then returned to Lakehurst, where he served a variety of assignments, including this observation flight aboard the Hindenburg. Mills would not be at Lakehurst the following year when the Hindenburg was destroyed by fire, however, having been assigned temporary duty at Newport News, VA for the fitting out of the USS Yorktown, which would later be lost at the Battle of Midway.

Several years later, in 1940, Mills would be promoted to Commander and appointed Commanding Officer of the Lakehurst Naval Air Station. In January of 1942, shortly after the United States entered WWII, Commander Mills was named commanding officer of the newly formed Airship Patrol Group One, and was then placed in command of Airship Wing Thirty in December of that year. By the end of 1943 he would be promoted again to the rank of Commodore and would serve as chief of the Navy’s blimp fleet, which played a key role in reconnaissance, submarine patrol and convoy escort for the Atlantic Theater. Following the war, he served as chief of the Naval Airship Training and Experimentation Command (CNATE) at NAS Lakehurst until he retired from the Navy in 1949.

By sheer coincidence, both “Froggy” Fulton and “Shorty” Mills passed away on the same day—October 24, 1975. The longtime friends and LTA colleagues were buried on the same day in Arlington National Cemetery.

Now serving once more as an official military observer, Mills paid particular attention to use of the Hindenburg’s elevators and rudders, meeting at length with Captains Max Pruss and Heinrich Bauer, two of the airship’s watch officers, to discuss operational specifics. He subsequently combined his notes with a running log of the flights to and from Germany, producing a detailed report for the Office of Naval Intelligence. Fulton, meanwhile, would file a similar report that focused more broadly on various operational and engineering features and procedures.

Eckener replaced Heinen and the flight was made successfully, but the working relationship between the two men never recovered. When the opportunity presented itself in 1922 for him to take a lucrative $500 per week position as an LTA instructor and test pilot over in the United States at the Lakehurst Naval Air Base, Heinen jumped at the chance. He moved to the States with his wife and daughter, and spent the next two years training Navy airshipmen to fly the United States’ first rigid airship, the ZR-1 Shenandoah. When the USS Shenandoah was lost in a storm over Ohio in 1925, the outspoken Heinen made headlines with his highly critical views on the disaster, suggesting that helium-saving reductions in the number of automatic overpressure valves on the gas cells led to the airship’s midair breakup.

Heinen himself dabbled in airship design, building a small non-rigid blimp dubbed the “Heinen Air Yacht”, which made some successful flights but failed to attract the hoped-for investors to put it into production. After becoming a naturalized American citizen in 1934, Heinen was given his commission in the Naval Reserve and served as an LTA instructor at Lakehurst until the beginning of World War II.

Like Mills and Fulton, Anton Heinen would file a report on the Hindenburg’s operations with the Office of Naval Intelligence. His observations focused on comparisons between German and American operational techniques, with his native fluency in German and his personal familiarity with many of the Hindenburg’s crew members allowing him a somewhat more nuanced perspective than that of many of the American naval observers who flew with the airship throughout 1936.

The fourth American observer aboard the flight was Karl Lange, a former Navy airshipman who now worked for the Goodyear-Zeppelin company. A blimp pilot who held a Lt. Commander’s commission in the Naval Reserves, Lange had a long familiarity with German passenger airship operations, having been in charge of station operations at Lakehurst during the LZ 127 Graf Zeppelin’s first landing there in 1928, and then overseeing the Graf Zeppelin’s landing and refueling at Mines Field in Los Angeles during the Graf’s round-the-world flight in 1929. On this Hindenburg flight, Lange would note his observations in a report that he would later file with Goodyear-Zeppelin, which was watching the Hindenburg’s flights with great interest in anticipation of its own plans to design and build airships for international passenger service.

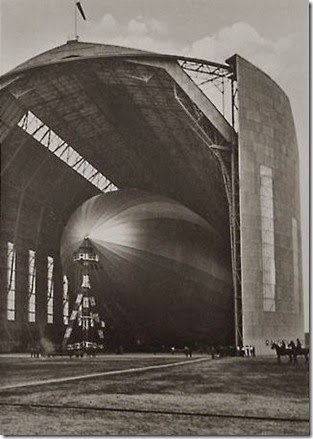

At 12:45 AM on August 17th, the Hindenburg was weighed off to bring her into precise equilibrium and, still attached to her mooring mast and her aft ride-out car, was walked out of the hangar onto the airfield. She was brought out tail first with her engines running slowly in reverse to assist the ground crew. Once clear of the hangar and in position on the airfield, the engines were shut down once again as final preparations were made. Meanwhile, the airplane carrying the Olympic newsreels, a bag or two of mail and the last few passengers arrived from Berlin. At approximately 1:00 AM, the Hindenburg was detached from her aft riding-out car and allowed to swing with the wind on her bow mooring spindle. The late-arriving mail, freight and passengers were all aboard by 1:20, and the ship was removed from her mast and weighed off one last time before the command came from the control car: “Schiff hoch!”

spectators line the autobahn alongside Rhein-Main airfield to watch.

(photo courtesy of the Luftschiffbau Zeppelin GmBH Archive)

The Hindenburg rose into the air at precisely 1:30 AM. When she had risen to a height of 210 meters, the navigator telegraphed the engine cars and their machinists began to start their motors one by one. However, the ship had risen into a temperature inversion, and by the time her second engine had started, the Hindenburg’s ascent had slowed considerably and she had drifted far enough to port that her tail brushed uncomfortably close to the end of the hangar. The crowd of onlookers held their breath as 500 kilos of emergency ballast was dropped forward, with 400 kilos being dropped aft. This checked the ship’s slow ascent, and she began rising steadily once more, and her remaining two engines were started.

The Hindenburg was now underway, setting a course for the English Channel via Cologne and Tilburg. The ship’s clocks were all set back to Greenwich Mean Time as she proceeded northward, and the command crew noted that despite the release of emergency ballast to counter the inversion on takeoff, the Hindenburg was now about 2 ½ degrees out of trim, up by the bow and approximately 7 tons heavy, owing to the release of hydrogen through her automatic overpressure valves as she rose to an altitude of 670 meters. The mechanic who was walking the keel on trim watch transferred fuel and water forward to redistribute the weight and bring the ship back into equilibrium. Meanwhile, given the lateness of the Hindenburg’s departure, most of the passengers retired to their cabins for the night.

First Day – August 17, 1936

Even with the change in course, the weather wasn’t particularly good on the first day out, and there wasn’t much for the passengers to see from the observation windows. They began to mingle, both in the lounge and in the pressurized bar and smoking room down on B-deck. In addition to the business executives like Jack Chrysler and Malcom Gibbs and the voyage’s minor news celebrities, Sam Foley and Alex Papană, there were also a number of families and family members traveling together.

Frank Louis Bailey Frances Bailey Ryder

Frank Louis Bailey from Brooklyn was flying with his niece, Frances Bailey Ryder, a 27 year-old graduate of Smith College in Massachusetts. The 70 year-old retired merchant was a seasoned world traveler—he had visited Egypt in 1926 and sailed home from Alexandria aboard the Red Star Line steamer, SS Lapland.

Theodor Othmar Schmid, a 46 year-old cotton broker from Zurich, Switzerland, was traveling to Shanghai with his wife, Mary Gertrude, and their 21 year-old daughter, Ellen Louise. Meanwhile, Carlos Stein, a 50 year-old merchant from Mexico City, on his way home with his wife, Eloisa. Canadian salesman Cecil French and his wife Helyn were traveling back to Victoria, British Columbia.

As would happen on any sea voyage, then as now, passengers chatted amongst themselves, struck up friendships, discussed the news of the day, business, the political situation in Europe, celebrity gossip, and so forth. As on a first class steamship, the stewards served bouillon in mid-morning, tea in mid-afternoon, and kept the passengers well supplied with drinks, playing cards and anything else they might require.

As they became better acquainted, passengers would often exchange addresses and autographs. Thóroddur Jónsson collected signatures from a number of his traveling companions on the inside title page of his passenger handbook.

Under his own signature, Jónsson collected 8 autographs from his new shipboard acquaintances: Jack Chrysler, the automobile heir; Rudolf A. Hütter, a German merchant from Cologne who was traveling to Detroit; Thurmann G. Hamilton, a 25 year-old New Yorker; Cecil French, the Canadian salesman; Miss Ellen L. Schmid, who was traveling to Shanghai with her parents; Cotton Mather, the Atlanta furniture dealer (who, beneath his signature, noted his home town along with “Good and Bad Furniture”); Anton Heinen, one of the US Navy observers; and attorney Samuel J. Foley, under whose name Jónsson noted, “Lindbergh Trial”.

Throughout the day, the six military observers—Student and Tschoeltsch from the Luftwaffe; Fulton, Mills and Heinen from the US Navy; and Lange from Goodyear-Zeppelin, inspected various parts of the ship, striking up conversations with various members of the Hindenburg’s engineering and deck staff. There were a larger number of crew members aboard this flight than usual, as was the case more and more often as the 1936 flight season progressed. With the new LZ 130 set to enter service the following year, and construction of even more passenger Zeppelins planned, the DZR needed to train and season crews more rapidly than ever.

To this end, several men were aboard the flight as navigator trainees, in addition to the regular watch rotation of three navigators. Hans Gluud and Gerd von Mensenkampff had served as elevatormen since the Hindenburg’s first test flight back at the beginning of March. Eduard Boetius had first flown as part of the Hindenburg’s crew in June, and had quickly developed into an exceptional elevatorman. The three men were now being trained in the art of aerial navigation in anticipation of promotion to the rank of navigator, the penultimate step to becoming a watch officer and a certified airship captain.

Navigator Max Zabel instructs Eduard Boetius (at left) in the

use of the Hindenburg’s system of gyroscopic compasses.

(photo courtesy of the Luftschiffbau Zeppelin GmBH Archive)

Christian Nielsen was already a navigator, and regularly flew aboard the Hindenburg’s sister ship, the LZ 127 Graf Zeppelin. However, as the Graf Zeppelin was scheduled to be removed from passenger service the following year in favor of the new LZ 130, a virtual carbon copy of the Hindenburg, Nielsen was aboard to cross-train on the cutting-edge navigational tools and techniques used by the Hindenburg’s navigators. (He would be aboard in the same capacity the following May when the Hindenburg burned at Lakehurst, but would escape virtually unscathed.)

Heinz Externbrink was also aboard, presumably as another navigator trainee or perhaps as an observer. Not much is known about him, however it is likely that he was the same Heinz Externbrink who published "Kaltlufteinbrüche in die Tropen" (Cold Air Surges in the Tropics) for Deutsche Seewarte in 1937. Given the DZR’s close working relationship with the naval observatory and its staff, it would make sense that Seewarte personnel would have occasionally flown aboard the Hindenburg to observe their long-range meteorological data being put to use. If this were indeed why Externbrink was aboard this Hindenburg flight, then there is the further possibility that this was also the same Heinz Externbrink who later served as the senior meteorological officer aboard the German battleship Bismarck in WWII, and who was lost when the Bismarck was sunk on May 27th, 1941.

In the Hindenburg’s engineering department, the military observers were led through the airship’s interior (even out into the fins) by Chief Engineer Rudolf Sauter and his flight engineers. Sauter, who had served as a flight engineer on the Graf Zeppelin since 1931, was still sharing duties with August Grözinger. The Graf Zeppelin’s venerable chief engineer had been temporarily assigned to the Hindenburg since her first test flights in March, but would be returning to his regular post aboard the LZ 127 by the end of September, leaving the new ship’s engines, her interior structure and her engineering staff in Sauter’s able hands.

The ongoing construction of new passenger Zeppelins allowed room for some of the more senior engine mechanics to move up to flight engineer roles. On this flight, Eugen Schäuble and Wilhelm Dimmler, both of whom had been Zeppelin mechanics since the Graf Zeppelin’s earliest flights almost a decade earlier, stood watch as Sauter’s engineering assistants. Schäuble had already been serving as a flight engineer for the past month or so, but for Dimmler (August Grözinger’s nephew and an excellent Zeppelin mechanic in his own right) this flight would be one of his first in the engineering role. Raphael Schädler, another long-time member of the Zeppelin family’s engine maintenance staff, would join Schäuble and Dimmler as Chief Sauter’s third engineering assistant on the Hindenburg’s next flight to Lakehurst in mid-September.

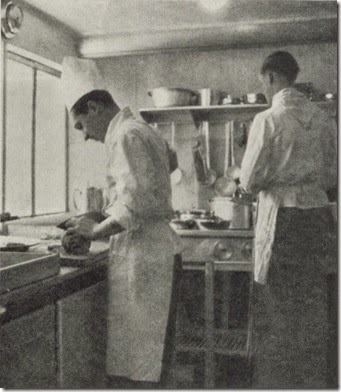

Meanwhile, Chief Steward Heinrich Kubis and his team of seven stewards looked after the passengers, answering endless questions as the travelers eagerly sought to learn what they could about this fast and luxurious new mode of transportation across the sea. To this end, the stewards led groups of passengers on guided tours of the Hindenburg’s interior throughout the flight. And, of course, there were the usual games of cards, chess and backgammon and discussions about business and world events that one would find on a regular steamship.

With limited visibility and lack of sights to view from the air, Thóroddur Jónsson kept track of the Hindenburg’s westward progress on the flight map that the stewards marked every few hours in the central foyer of A-deck, next to the brass bust of the airship’s namesake, the late German President Paul von Hindenburg. As the foyer map was updated, Jónsson copied the Zeppelin’s flight path onto the smaller map included in his official passenger brochure. He continued to trace the Hindenburg’s progress across the North Atlantic until just before the airship reached Boston on August 19th.

After leaving the English Channel at Plymouth at about 9:00 in the morning, the Hindenburg had turned south-southwest, with the Bay of Biscay to port and the open sea to starboard. She passed the Spanish coast near Ferrol and A Coruña in the early evening, giving the passengers a brief glimpse of the Iberian peninsula. With the sun beginning to set, the helmsman then turned the Hindenburg west-southwest, out to sea toward the Azores.

Second Day – August 18, 1936

According to Jónsson’s log notes, the Hindenburg reached the Azores at about 4:00 the next morning, August 18th. The weather had cleared somewhat, and so the watch officer telegraphed the engine mechanics to slow their engines and ordered the helmsman to swing the ship to the west along the archipelago’s southern edge to give passengers a view of the islands as the sun rose.

A fine continental breakfast was served beginning at 8:00, consisting of freshly baked rolls (served with butter, jam and honey), eggs, cheese, sausage, fruit, coffee, tea, juice, etc. As the stewards rang the chime calling the passengers to the dining salon, Dr. Edward Buetzow, a dentist from Pittsburgh, PA, was addressing a postcard to Reverend Leonard O. Burry, pastor of St. John Evangelical Lutheran Church in Carnegie, PA.

“Tuesday, 8:00 AM

Great trip; X just my bunk. Thought you might like a stamp.

Flew a great deal in Europe, & home.

Greetings,

Dr. E.W. Buetzow”

This particular postcard, marked as “Schlafkabine im Luftschiff Hindenburg” (sleeping cabin in the airship Hindenburg) showed a rare color photograph of one of the Hindenburg’s passenger cabins. Seen below in a scan from an unused copy of the same postcard, the photograph shows the Pullman-style bunk beds at right (the “X” mentioned in Buetzow’s note indicated that his was the upper bunk), a pull-cord on the wall with which passengers could ring for a steward, a retractable table top in the rear wall, a small folding stool, and a mica sink at left with hot and cold running water. The curtain for the closet can also be seen in the left rear corner of the photo, though the closet itself was only deep enough to hold a few suits or dresses.

In addition to Dr. Buetzow, there were also a number of other professionals aboard, including another doctor. Mary Layman was a pediatrician from San Francisco who worked as a charity volunteer. The 52 year-old physician had studied medicine in Munich, and still traveled occasionally to Europe for both study and recreation.

Dr. Mary Layman Marie Fuhrmann

47 year-old Marie Fuhrmann, a high school teacher, was on her way home to her husband Otto in Elmhurst, NY. Another native New Yorker, Elsie Harwood, was also returning home. The 42 year-old Brooklynite was a secretary for a lead mining company, and had sailed to Europe aboard the Queen Mary a couple of weeks earlier, arriving in Southampton on August 3rd. It is unknown whether she was in Europe on business, to attend the Olympics in Berlin, or on vacation.

Also on their way to New York were two Japanese travelers, Dr. Sozaburo Etoh, a 42 year-old physician from Tokyo, and Kiyoshi Uratani, a 24 year-old professor from Osaka. Both gentlemen were traveling as guests of Japanese Government Railways, Japan’s rail ministry that oversaw that country’s national railway system.

Ralph Bernard Gough was a 25 year-old actuary from London. After graduation, he had entered the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve as a wireless operator. Sadly, Gough would be stationed aboard the Royal Navy destroyer HMS Exmouth three and a half years later when it was torpedoed by a German U-Boat, the U-22, and sank with all hands in the North Sea off of Tarbat Ness, Scotland.

After leaving the Azores behind, the Hindenburg continued to fly on her original west-southwest course until about noon. As the airship turned northwest toward Newfoundland, passengers sat down to a lunch that, according to a surviving copy of that day’s menu, started with a Consommé Navarin, a rich beef consommé garnished with small crayfish tails, green peas and chopped parsley. For the main course, Chef Xaver Maier had chosen peasant style mutton ribs in Lorenz marinade, served with a green salad. Afterward, passengers sipped on mocha and enjoyed a dessert of fruit crème with raspberry dip.

(photo courtesy of the Luftschiffbau Zeppelin GmBH Archive)

The day passed relatively uneventfully, until just about the time the passengers were seated for dinner. The mechanic on duty in the Number 4 engine car, portside forward, stopped his motor after noting a sudden rise in oil pressure. The engine was given a thorough once-over, and the source of the problem turned out to be that a piston skirt had frozen after its piston pin had broken – almost the exact same problem that had ended up hobbling three of the Hindenburg’s four engines during the return leg of the first flight to South America earlier that year. However, this time the mechanics were able to repair the engine within about three hours, and the motor was brought back up to its normal cruising speed of 2100 RPM.

Meanwhile, unaware of the problems that the mechanics were having, the passengers had tucked into another fine dinner from Chef Maier and his cooks. There was a cream soup Judic (made with finely shredded lettuce, chive and chervil), and poached eggs Florentine for the first course. For the main course there was a Strasbourg filet with a green salad, and then chilled fruit and cookies for dessert. And of course, from the Hindenburg’s wine “cellar,” there were bottles of the finest Rhine and Moselle wines, as well as Burgundy, Bordeaux and champagne.

(photo courtesy of the Luftschiffbau Zeppelin GmBH Archive)

All meals were cooked in the ship’s kitchen, downstairs on B-deck, and sent up to the dining room’s serving pantry via dumbwaiter. Alfred Grözinger, one of Chef Maier’s cooks and the son of Chief Engineer August Grözinger, would later recall a rather unique challenge posed by meals like this evening’s dinner. The kitchen was all electric, including the oven. Since the Hindenburg’s designers had done everything possible to minimize the risk of fire, the oven had an automatic shutoff mechanism that turned the heat off once it had been above a certain temperature for a rather brief length of time. This was, of course, a real problem when it came to broiling steaks like the Strasboug filets that were served with this particular meal. The cooks would just get the steaks sizzling when the oven would shut off. So, they would turn the oven back on, cook the steaks a little longer, and the oven would shut off again. According to Grözinger, it was an exercise in supreme patience to prepare steaks for 50 some-odd passengers.

Just before sunset, the Hindenburg encountered growing thunderheads, and within the hour she had begun to encounter rain squalls. Captain Lehmann ordered the water lines opened between the external rain gutters and the storage tanks, intending to pick up water from one of the lighter squalls. However, the squall built up into heavy black rain clouds and Lehmann thought better of the plan, instead ordering the helmsman to skirt around the storm.

Commander Garland Fulton, and Lt. Commander George Mills were in the control car at the time. Fulton noted the marked improvements in the methods now used by the Hindenburg’s command crew to determine the proximity of thunderstorms. When Fulton had flown aboard the LZ 127 Graf Zeppelin three years earlier, ship’s commander Dr. Hugo Eckener had relied almost entirely on visual observations through the control car windows, only occasionally consulting a weather map. Now, along with along with the latest weather maps from Deutsche Seewarte, Captain Lehmann and his team of watch officers and navigators used the Hindenburg’s state-of-the-art radio direction finding apparatus to check the intensity of static when in the vicinity of thunderstorms. Direct window observations, Dr. Eckener’s primary tool for navigating the Graf Zeppelin through inclement weather, was now used mainly when the helmsman was maneuvering the Hindenburg past the most threatening cloud formations.

the control car’s navigation room during an earlier flight in 1936.

(photo courtesy of the Luftschiffbau Zeppelin GmBH Archive)

Third Day - August 19, 1936

As the weather ahead continued to deteriorate, with lightning crackling ahead and to the north, further examination of the weather maps indicated that the Hindenburg was likely due to meet a cold front within the next several hours. Captain Lehmann then retired to his cabin and got what rest he could until the watch officer rang his cabin telephone to inform him that the ship was approaching the front. When asked whether they should turn and fly parallel to the front until daybreak, or continue on toward the front, Lehmann ordered that the ship maintain its present course, then made his way back to the control car approximately half an hour later.

The Hindenburg began to enter the front about an hour after Lehmann returned to the control car, with the helmsman zig-zagging to avoid the darkest patches of cloud. Despite one severe gust that rolled the ship slightly to port, the ship entered the front smoothly and with a minimum of disturbance for the passengers. Meanwhile, the ballast recovery system was able to collect 4 ½ tons of water, topping off the ship’s ballast storage tanks in about 20 minutes time.

Land was sighted at about 11:00 AM, local time. The Hindenburg made landfall at Cape Sable Island in Nova Scotia, and Captain Lehmann ordered a course set for Boston. It is shortly after this that Thóroddur Jónsson’s map of the Hindenburg’s flight path ends. By now, Jónsson and the other passengers would likely have been preoccupied with packing their bags so that they would be free to line the observation windows and watch the sights as they skimmed past the New England coast, on their way to Lakehurst.

The Hindenburg arrived over Boston just after noon, to the delight of the lunchtime crowds. The only Bostonian aboard this flight, 30 year-old Louis J. O’Malley, undoubtedly peered downward, trying to spot his home on Beacon Street as the airship circled the city. Then the Hindenburg continued along the coast over Rhode Island and Connecticut, on her way to New York.

The Hindenburg was over New York by 4:15 PM and, as had become tradition on the airship’s North American flights, Lehmann treated the passengers to an hour-long cruise over New York Harbor, Battery Park and the city’s forest of skyscrapers. As she passed overhead, steam whistles atop the buildings and on the ships in the harbor blasted skyward in greeting.

Then it was time to fly down the Jersey coast toward Lakehurst. The Hindenburg had some time to kill while the landing crew was mustered and positioned at the air station’s mooring area, so she cruised leisurely down the Jersey shore, passing over Asbury Park, Point Pleasant, Tom’s River and Atlantic City. Then the airship turned to the northwest and made her way toward her landing field at Lakehurst.

At Lakehurst, preparations had been made to receive the Hindenburg, and the ground crew was now in position and waiting to moor the ship. Commander Charles E. Rosendahl, the air station’s Commanding Officer, would be flying back with the Hindenburg that night, along with Lieutenants George Watson and Alex McIntyre. The three men would record and report on their observations just as Fulton, Mills and Heinen had done.

However, with the Hindenburg running behind schedule due to her late start from Frankfurt and the intermittent headwinds she had bucked on her way across the Atlantic, landing her was just the beginning. Lt. Commander C.V.F. Knox, who would be in charge of replenishing the Zeppelin with fuel, water and hydrogen, was planning on setting a record for servicing the ship for her next flight. Although it was obvious that the Hindenburg would not be making her scheduled midnight departure time, Knox estimated that he and his crew could have the airship gassed up and fueled in a minimum time of 7 hours and 47 minutes. Between the servicing time and the loading of passengers and provisions, that would place the Hindenburg’s departure at sometime between 4:00 and 4:30 the following morning. Not bad, considering the fact that the airship had taken off 5 ½ hours late from Frankfurt, waiting for the last-minute shipment of Olympics newsreels.

Although most of the passengers for the Hindenburg’s return flight were currently waiting at the Biltmore Hotel in New York, from which they would later be ferried down to Lakehurst by DC-3, two “passengers” were already at Lakehurst by the time the airship arrived. Charles Belden, of the Pitchfork Ranch in Wyoming, had flown into Lakehurst earlier that day in his own private airplane. Known as “The Antelope King”, Belden would regularly relocate pronghorns from his ranch to zoos across the United States via airplane. On this day, he had brought two baby pronghorns to Lakehurst. The little antelopes would be carried across the ocean in the belly of the Hindenburg on her return flight, and taken to their new home at a zoo in Hanover, Germany.

pronghorn fawns as the Hindenburg descends in the background.

The Hindenburg approached the Lakehurst landing field at about 7:00, and was moored to her mast by 7:30, exactly 71 hours after her departure from Frankfurt. She was not brought into Lakehurst’s gigantic Zeppelin hangar, however—her command crew preferred to leave her at her mast out on the airfield to enable her to depart as soon as she was reprovisioned.

Meanwhile, Thóroddur Jónsson made some final notes on the flight log page in his passenger booklet. He had noted the time the Hindenburg had passed several landmarks along the way, and jotted down a number of vital statistics about the flight:

17 August - 9:03 AM – Plymouth

18 August - 4:00 – Asora (Azores)

19 August - 7:00 - Halifax

Flight statistics:

4,102 nautical miles

7,600 kilometers

67 kilometers / 51 minutes from New York

Average speed: 111 km/h

Slowest cruising speed: 60 km/h

Fastest cruising speed: 130 km/h

Arrived 20:20 American time

Lt. Commander Knox and his men, joined by members of the Hindenburg’s crew, began to load the airship with fuel, water and hydrogen as soon as the passengers had disembarked and the ship’s freight had been offloaded (including Alex Papană’s airplane.) As it turned out, Knox and his team were even more efficient than they had expected. In fact, they had the Hindenburg’s gas cells topped off with fresh hydrogen and her fuel and water tanks filled in a record 5 hours and 20 minutes. Her 57 passengers aboard and her 250 pounds of mail and 300 pounds of freight (plus two baby pronghorns!) stowed, the Hindenburg was weighed off and made her ascent for her return flight to Germany at 2:33 AM, August 20th, 1936 – 7 hours and 3 minutes after she had landed.

Wasting no time, the Hindenburg bypassed New York altogether and flew straight out to sea immediately after casting off. One of her passengers, Mr. K.H. Royter, snapped a photo of the sun breaking through the clouds at dawn as the Hindenburg soared serenely homeward over the North Atlantic.

(taken from the airship Hindenburg on her 7th eastbound crossing in 1936 by K.H. Royter)

Thóroddur Jónsson returned home aboard the Queen Mary at the end of August. He saved his passenger booklet as a souvenir of his Hindenburg flight, later handing it down to his family. His import/export business continued to thrive, and in 1939 he married Sigrúnu Júliusdóttur, with whom he had four children. Jónsson passed away on August 13, 1976 at the age of 71.

LZ 129 Hindenburg

7th North American Flight

August 17-19 / 20-22, 1936

CREW MEMBERS

Ship’s Commander

Captain Ernst A. Lehmann

Watch Officers![clip_image002[4] clip_image002[4]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEjRjARoLuFNtIJEm5HHpJwkVrtezu8IJrtDz1C4JOZO7aweo8YmfLFz4YT6NrHTXx8hAEMW-UwmqvJAKWrLlFj8du70DeevzXlxlqN4MdPiSgKVdnfbNrBeZ-t8WyndYuKtPxSihQwEcVM/?imgmax=800)

![clip_image002[6] clip_image002[6]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEisVexa3OF2NPyAt2suDal4hKU90RccGObwomhfb8lnchLvtAskD7pGdldc5btVF3MuVWL9RcoyPzyBP2LEjkWLS53S6W9dN4UVJq4hk7OMcU47ROuNzXUU8_uyVo28tVS9kgZ2CVVGiQU/?imgmax=800)

Captain Max Pruss Captain Albert Sammt Captain Heinrich Bauer

Navigators![clip_image002[10] clip_image002[10]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEhMotrzRdeyWSFDxAFnaz7ck2UhfRwBKwtv4eA07qdjFhJynMk3H27jX26GU6RNtDSOLOdx78QQ7g12ChSJHDOrLQRbjL-oPoFWn1RjIbWCbaQaB-Oaq2wddolF1tbxSiR1m-e3a7MLGek/?imgmax=800)

![clip_image002[8] clip_image002[8]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEi2Qica6Td-IbXz3vJkz_AXJMWbmUiEkIqZE9lgLYSF4fDoyj-Z_MszgqcxJWJFHJ9426tKHX8TGyukRcReviWj1-K6ztboT6UxEMmdan1BANCnUT3wouMWtFka9vnWP2VQN5PG22qUYZo/?imgmax=800)

Max Zabel Walter Ziegler Franz Herzog

Elevatormen![clip_image002[14] clip_image002[14]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEiK43_airECSof9Aqo2-jsSrOrArDY8ksE0qH02OV4FwFC4aiv_Rp1za7fztPLcjUPa1PEeowHRpTzMAUQMeUPttkLT4-nwLgf1nQcwycOVZtYOaG2Jw7iMOXIcfMurIjP4b9Phhu9TJbA/?imgmax=800)

![clip_image002[20] clip_image002[20]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEiDsDu_Lc08-VoNU7XVfRDP6L-vSnzCpTIGRvXsaAzFKz8JQv-jFWyr0iUEuauwqj3gtI_kseH51G_E2CsFtgSOLzgjmvZfypUs4yVI5SkKo-01P6GbMjsACbzUCZo9XaRKldWtzZ6-H3Y/?imgmax=800)

Johann Geier Ernst Huchel Walter Schulz

Helmsmen ![clip_image002[22] clip_image002[22]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEh-l4p11rqWvxT9Rib0NAxXPK9qn1TzuM-I2RVH1gkEJdHuKeYt2fe6ad25dXYOCwcM2SGER_1t5YKrHy8DBO89mfU1jN_UkCi6SZPAJY0wXYQ3q8Hnvtg1IUsxwdXlDmRtgHAUYA2YvRI/?imgmax=800)

![clip_image002[24] clip_image002[24]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEhlcdvjcGJz6OuBZJ5aEAecm1pn-iKR_SWi-NMFwF9T5VBVr9x60wMGNK4BJsqB7Kpkbth5VXmIx4MO7-xBn2bE41CWG-sPcRN-8bOWFCkM-28tmVxP538zwlHnHqZOYndimgSJ9yasMws/?imgmax=800)

Kurt Schönherr Helmut Lau Ludwig Felber

Radio Operators![clip_image002[28] clip_image002[28]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEj1oa-Jz4rn_bOiB2DywdkNxYCN7ROXtjEaVcClmpOTUj-0OuchvZZq0Y0w2NNFDhdBIFoYpIuI-vU1VMuUB0PtBDXHaDHs3m0kZ7YDURJRO8IZrpYErLYCFVKAOHh5tqzd5peKlpUBth4/?imgmax=800)

![clip_image002[34] clip_image002[34]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEjC-sdirz2ZgU0UtLixKpXzvqgKodz9ux1U3J3Mbn8dy4TQHrJgfo8uW6sPNZD7QcDLJXURid2dcSPIZGfGEFuEbp88xfFzPd66tkIYHN3dXuc3xpolsNKqMjxZIEeTDIsLMup9d7WgkVs/?imgmax=800)

Willy Speck Egon Schweikard Ernst Hartwig

(Chief Radio Officer)

Chief Engineer

Rudolf Sauter August Grözinger

Flight Engineers

Eugen Schäuble Wilhelm Dimmler

Engine Mechanics

Engine Car #1: ![clip_image002[44] clip_image002[44]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEi0rYK9Z4BdtNCu9vHK_NKMQNIHwZyx9M9GKOxfboR3OZDrk2NE6B15MJEGJP71HdZY_yXmfLBIiY0Cg4ccgt15z2GhWMcUIZGfjd7rD9jc_HawZR0HKiURabGjYPaJDJmSBEa2psHLmDU/?imgmax=800)

![clip_image002[46] clip_image002[46]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEjrYnIpeSPXIRaRWuq5dhUlMKaznK5y4tX449EA4zbel0H3t-ZHaNgYEfCpDsUoOWemq_0Y7Ox31ZjNEwjfcLfb6kLeC-qBNF7AFKrp5Ov-pCW_f9Gk4523TUkJuuMyAhPN2hCmxjmeKLs/?imgmax=800)

Josef Schreibmüller Eugen Bentele Jonny Dörflein

Engine Car #2:

Hans Fiedler Richard Halder August Deutschle

Engine Car #3:

Raphael Schädler German Zettel Willi Scheef

Engine Car #4:

Adolf Fischer Walter Banholzer Willi Döbler

Trim Watch:

Hermann Rothfuss Richard Kollmer Alfons Schäfer

Electricians: ![clip_image002[69] clip_image002[69]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEhrzGdM9zQkBAHeCdu26Gpo3MTO7Zv7CeUj6dr-38EJrio23TdLPT5TnjIjO1sjJnxaVvNvdNIs2LzqYqb9yGghHlxunZIYC4zb-ggbG2ZjTKqOZ9o6NtKcljGk7bz1FalBQsYav9BB_88/?imgmax=800)

![clip_image002[71] clip_image002[71]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgEhbmZmnbUZa6kgEB4lIk-bkGwEpCzn7_0diTH6fJYVV2RQiE4qYWIwkJmg1sXYEu5ijoksKJ_FfIZHQ9sNB8oaWI5DRjwOu909rOBi0KaGO0VqDWmvSuERDnLJWwXnJnUCq3-giFwnJo/?imgmax=800)

Philipp Lenz Georg Kunkel Karl Butscher

(Chief Electrician)

Riggers

Ludwig Knorr Hans Freund Erich Spehl

(Chief Rigger)

Stewards

![clip_image002[80] clip_image002[80]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEhNBkEfTmV3RLbzgYSZK7Al6E2j1mDA6DExW3t2-JCTjisjUSKRY0EmOgWD-vJDUQODjX2WtcPVbP_IldLuIhU6mhRdQfiComflwyT8Ddc92Yi342tAliH4tNcoGn_olhK_nb1AbDiV5QY/?imgmax=800)

Heinrich Kubis Eugen Nunnenmacher Max Henneberg Wilhelm Balla

(Chief Steward) ![clip_image002[82] clip_image002[82]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEhxjbyLERInQusjms_KdzbXI4m8Rn2yhj9FfdwMYMQpcG5I5_8kPsO_Nggm8U3iViBkPNHF07yJMf4g9MmNqAOTCFFkNKa5qZtdaMojpQbhnjYBp9CCWTL0anOJeR-1PyQF1xWUTg4-8AA/?imgmax=800)

Fritz Deeg Anton Riegger Severin Klein Max Schulze

(bar steward)

Cooks

Xaver Maier Alfred Grözinger Albert Stöffler Walter Wintergerst

(Head Chef)

Miscellaneous (Trainees/Observers)

Christian Nielsen Hans Gluud Gerd von Mensenkampff

Eduard Boetius Heinz Externbrink

Passengers (Westbound – Frankfurt to Lakehurst)

Dorothy Adair

New York City, NY

Frank Louis Bailey

Brooklyn, NY

Age 70 (Born March 5, 1866 in Brooklyn)

Traveling with niece Frances Bailey Ryder

Arlene Belvoir

Idaho Falls, Idaho

Age 45

Naturalized citizen by marriage to Frank Belvoir – May 18, 1911

William John Brandenburg

Los Angeles, CA

Age 61 (born December 28, 1874 in Chicago, IL

Engraver (electrotipping)

Dr. Edward W. Buetzow

Pittsburgh, PA

35 years old

Dentist

Jack F. Chrysler

Detroit, MI

Age 24

Youngest son of Walter P. Chrysler, founder of Chrysler Motor Company

Langhome B. Dick

Philadelphia PA

Age 47 (born Feb. 6, 1889 in Philadelphia)

James W. Elwood

Omaha, NB

Age 61 (born February 20, 1875 in Omaha)

Taxidermist

Dr. Sozaburo Etoh

Tokyo, Japan

Age 42

Representative of Japanese Government Railways

Visiting the Japanese Tourist Bureau in New York

with Kiyoshi Uratani

Laurance K. Etter

10161 Hasskell Ave. San Fernando, CA

Age 30 (born October 12, 1905 in Wickenburg, AZ)

Julie Fleischhauer

Köln, Germany

Age 42

Samuel John Foley

New York City, NY

Age 46 (born April 7, 1891 in New York City)

District Attorney, Bronx County NY

Worked the Lindbergh baby kidnapping

Cecil Ernest French

Victoria, BC, Canada

Age 38 (born 1897)

Salesman

Helyn B. French

Victoria, BC, Canada

Age 39 (born 1897)

Marie Fuhrmann

Elmhurst, NY

Age 47 (born June 20, 1889 in New York City)

High school teacher

Commander Garland Fulton

Lakehurst, NJ

Age 46 (born May 6, 1890 in Oxford, MS)

Head of Navy Bureau’s Lighter-Than-Air Design section

Official military observer

Andrew Gahagan

New York, NY

Age 45 (born October 10, 1890 in Chattanooga, TN)

President of a metal manufacturing firm

Malcom G. Gibbs

Washington, DC

Age 48 (born September 20, 1877 in Union City, TN)

President of a drug store chain

Ralph Bernard Gough

London

Age 25 (born 1912 in London)

Actuary

Thurmann G. Hamilton

New York NY

Age 25 (born May 10, 1911 in Philadelphia, PA)

Elsie Harwood

Brooklyn, NY

Age 43 (born Sept. 11, 1892 in Brooklyn, NY)

Secretary for a lead mining company

Gertrude Heindrichs

New York, NY

Age 43 (born in Germany)

Naturalized November, 1927 in New York

Anton Heinen

Lakewood, NJ

Age 51 (born in 1885 in Wilhelmshafen, Germany)

Naturalized in 1934

LTA instructor, Lakehurst Naval Air Station

Lt. Commander, US Naval Reserve

Helen J. Horton

New York NY

Age 46 (born Feb. 13, 1890 in Covert, NY)

Rudolf Arnold Hütter

Köln, Germany

Age 31

Merchant

Jean Johnson

Montreal, Quebec, Canada

Age 38

Thoroddur Jonsson

Reykjavik, Iceland

Age 31 (born May 6, 1905 in Þóroddsstöðum, Iceland)

Merchant

Charles Kammann

St. Louis, MO

Age 75

Carl Klooss

Cincinnati, OH

Age 48 (born in Germany)

Naturalized October 18, 1923 in Cincinnati

Metal manufacturing executive

Lloyd Knapp

Monroe, MI

Age 38 (born April 16, 1898)

Paper mill manager

Ernest Kresse

Brooklyn, NY

Age 62

Naturalized June 16, 1917 Brooklyn NY

Shoe manufacturer

Karl Linwood Lange

Washington, DC

Age 38 (born May 12, 1898 in Ipswitch, MA)

Representative, Goodyear-Zeppelin Corporation

Lt. Commander, US Naval Reserve

Dr. Mary Layman

San Francisco, CA

Age 52 (born August 19, 1884 in Alameda, CA)

Pediatrician

Harry “Cotton” Mather

Atlanta, GA

Age 52 (born August 5th 1883 in Elkhart IN)

Proprietor, Mather Brothers Furniture

Lt. Commander George Henry Mills

Naval Air Station, Lakehurst, NJ

Age 41 (born August 5, 1895 in Rutherfordton, NC)

Dr. Constantin I. Motas

Bucharest, Rumania

Age 49

Engineer

Key player in the nationalization of Rumania’s natural gas fields

Elena Motas

Bucharest, Rumania

Age 46

Louis J. O’Malley

Boston, MA

Age 30 (born April 7, 1907 in Boston)

Alexandru Papană

Bucharest, Rumania

Age 30 (born October 18, 1906 in Rumania)

Stunt Pilot

Richard Peabody

New York City

Age 32 (born November 1, 1904 in New York City)

Stockbroker

Ned Raynolds

Fairlawn, OH

Age 17 (born November 18, 1918 in Akron, OH)

William G. Rice

Philadelphia, PA

Age 70

Civil Engineer

Dr. Wilhelm Rohn

Hanau, Germany

Age 49

Engineer

Led the development of an innovative vacuum smelting process for WC Heraeus, a platinum/precious metals smelting company in Hanau.

Frances B. Ryder

New York, NY

Age 27 (born December 21, 1908 in Brooklyn, NY)

Traveling with her uncle, Frank Bailey

Johannes Schlieper

München, Germany

Age 49

Banker

Theodor Othmar Schmid

Zurich, Switzerland

Age 46

Merchant

Mary Gertrude Schmid

Zurich, Switzerland

Age 38

Miss Ellen Louise Schmid

Zurich, Switzerland

Age 21

Carlos Stein

Mexico City, Mexico

Age 50

Merchant

Eloisa Stein

Mexico City, Mexico

Age 43

Charles L. Stevens

Wilbraham, Mass.

Age 39 (born November 6, 1899 in Stoneham, MA)

Headmaster of Wilbraham Academy

Col. Kurt Student

Rechlin, Germany

Age 46 (born May 12, 1890 in Birkholz, Germany)

Kommandant – Rechlin Airfield

Official military observer

Henry Swensson

Los Angeles, CA

Age 51 (born Oct. 11, 1884 Racine, WI)

Alfred Thiemann

Dortmund, Germany

Age 50

Merchant

Ruth Thomasson

Chattanooga, TN

Major Ehrenfried Tschoeltsch

Jüterbog, Germany

Age 43 (born March 4, 1893 in Greifswald in Pommern, Germany)

Flight instructor for reactivated Luftwaffe officers in Döberitz and Königsbrück

Official military observer

Kiyoshi Uratani

Osaka, Japan

Age 28

Assistant

Representative of Japanese Government Railways

Visiting the Japanese Tourist Bureau in New York

with Dr. Sozaburo Etoh

Eugen Wilhelm Walter

Essen, Germany

Age 37

Engineer

Passage paid by Krupp, AG

Passengers (Eastbound – Lakehurst to Frankfurt)

Mr. Preston R. Bassett

Mr. George Borg

Dr. Harry J. Brayton

Mr. G.C. Brock

Mrs. M. Bronner

Mr. George W. Brown

Mrs. George W. Brown

Miss Grace Brown

Mr. Harvey D. Burrill

Mr. Harry T. Clews

Mr. Paul Damm

Miss Edna Donnell

Mr. Fred F. Emisch

Mrs. Fred F. Emisch

Mr. Friedrich Wilhelm Engels

Mr. Fred Frey

Mrs. D. Edwin Gamble

Miss Nellye M. Gray

Miss Eulalie C. Harris

Mr. Bernhard Herlan

Dr. Wm. Hoehn

Miss Jennie Holde

Mr. John M. Holmes

Mrs. Robert Hunter

Miss Caroline Hunter

Mr. Ernst Jung

Mr. T.L. Kelly

Mrs. T.L. Kelly

Mr. Norman C. Lee

Lieut. Alexander MacIntyre

Mr. Louis Martinz

Mr. Frank Masotte

Mr. W.E. Mayer

Mr. Meincke

Mr. F.W. von Meister

Mr. Paul Mestern

Mr. Robert Muller

Mr. J. Outhet

Mrs. W. Ellis Peterson

Mr. D.K. Pfeiffer

Dr. Eduard Rischar

Commander Charles E. Rosendahl

Mr. K.H. Royter

Miss Elinor M. Ryan

Mr. John R. Sofio

Count Laszlo Szechenyi

Miss P. Theodora Walsh

Lt. George F. Watson

Mrs. Alida White

Mr. L.B. Whitfield

Captain Gill Robb Wilson

Mr. S.K. Wolf

Dr. Ing. S.J. Zand

Special thanks to Mr. Steen Blöndal for not only sharing his grandfather’s passenger list with me and allowing me to use selected scans to illustrate this article, but also for providing me with biographical information about his grandfather, Thóroddur Jónsson.

Thanks also to Dr. Cheryl Ganz for providing the scan of the written side of Dr. Edward Buetzow’s postcard to Rev. Leonard Burry, and also for sharing the in-flight menu from August 18, 1936.

![clip_image002[12] clip_image002[12]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEh38GibfTB012AUqmO-cU1xgF94qyr6iD-WqMaJDOWB32CYI4Wzx73WmOfD1aGKTmG2nGuG23mIIK2CNqV3O3ohCzw0RlLYEIUM-EnokR4q1V7eGVWvYsLLko2e6pUJddTUmYTqt-yLE0w/?imgmax=800)

![clip_image002[38] clip_image002[38]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEhMx5sWlWCMTUTEARFT65NHym_XSfrmUt0ZEVZIlRyn7_XxKmgznyuJvTaOraDhYMEFGgiaW_2jBIcMl3j1vq6JjIDJuGj-CGL9hzjEHmDCsT-BSkprivQyqvuq19CbEl2HZYRa9yAClGw/?imgmax=800)