On the afternoon of May 6th, 1937, as the German passenger airship Hindenburg circled New York City, two young men in the city’s Chinatown district were preparing to follow it to its destination. Foo Chu, a 16 year-old first-generation Chinese American, borrowed his family’s Leica 35mm camera and climbed into his friend Benny Kimlau’s car – a brand-new Lincoln that Kimlau wanted to break in with a road trip to the Naval Air Station at Lakehurst, NJ, where the massive Zeppelin was scheduled to land at about 6:00 PM Eastern Daylight Time.

By the time the two young men reached their destination, the Hindenburg was preparing to land, having been delayed an extra hour by thunderstorms. As Chu and Kimlau parked in the visitor’s area next to the air station’s massive airship hangar, the dirigible was approaching its mooring mast. It was approximately 7:20 PM. Chu, still standing in the rain-soaked parking lot, raised his Leica and snapped a shot of the Hindenburg hovering out over the airfield, preparing to drop her landing ropes.

Foo Chu made his way closer to the fenced-in area just beyond the hangars where friends, family and onlookers watched the giant airship being pulled down toward her mast. A gust of wind had just pushed the Hindenburg further out over the airfield, and Chu stood on the sidewalk next to one of the airplane hangars. Approximately five minutes had passed since he’d taken his first photo. Suddenly, a small burst of flame appeared near the Zeppelin’s tail fins, and almost immediately the entire aft half of the ship was in flames.

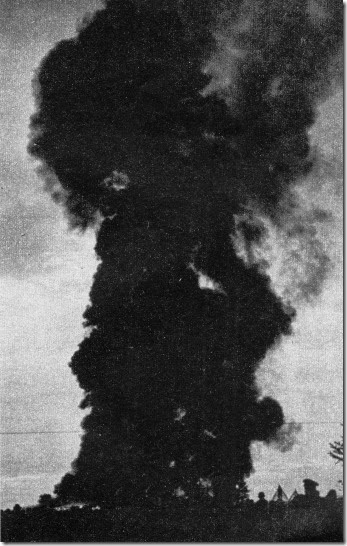

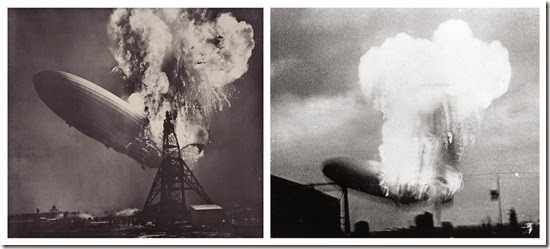

Raising his camera, Chu took his next shot before he had had a chance to steady his hands. The resulting image, showing some motion blur, caught the Hindenburg just as the fireball began to rise above the ship and its tail began to drop to the ground.

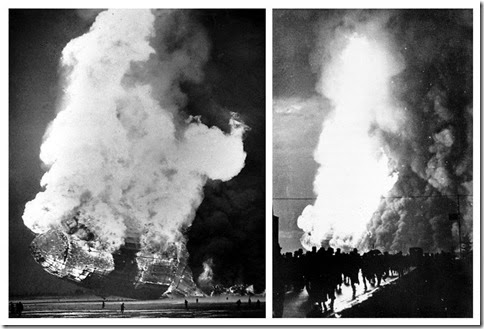

Then Chu began to wind the film and snap the shutter as quickly as he could. His camera now steady, he managed to take seven more photographs in the half a minute that it took for the burning Zeppelin to crash to earth. As you will see in the photos below, he also captured the additional drama of horrified spectators fleeing from the roped-off visitors’ area fleeing back along the sidewalk where Chu and Kimlau stood.

Foo Chu crash photo #3

Foo Chu crash photo #3

Most of the professional photographers on the scene that evening were located further out on the airfield near the mooring mast, and were shooting with bulky sheet film cameras like the Speed Graphic. The 4”x5” negatives produced crisp, detailed images, but they were large and cumbersome and required that a new sheet film holder be inserted for each shot. Therefore, the majority of the news photographers were able to take between one and three photographs in the 34 seconds that it took for the Hindenburg to meet her fiery end, depending on how quickly they could switch film holders.

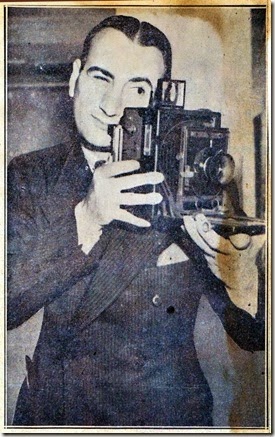

Murray Becker, AP photographer, is shown above with his Speed Graphic sheet film camera in a news clipping from a few weeks after the disaster. Becker happened to have his camera trained on the Hindenburg at the moment it caught fire, and was able to snap his first picture when the airship was still on an even keel, several seconds prior to Foo Chu’s first photo…

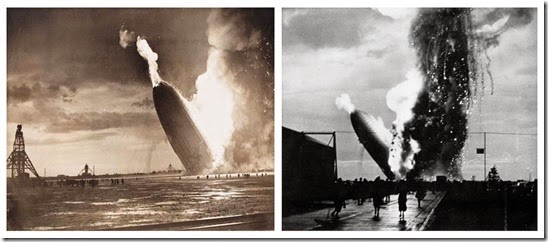

Becker’s second photo, which eventually won him an award, was taken a split second after Chu’s second image as fire erupted from the Hindenburg’s bow…

And finally, Becker was able to get one last shot at almost the exact same moment that Chu was snapping his sixth crash photo…

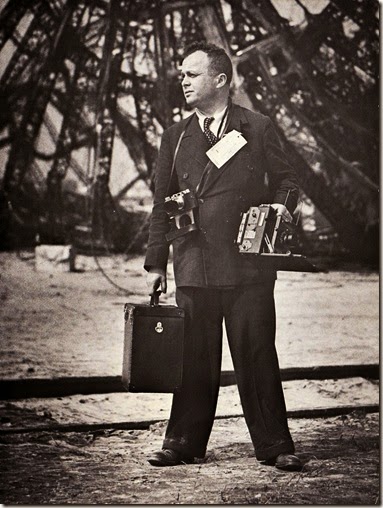

Another news photographer, Sam Shere from UPI, is shown below posing in front of the wreckage of the Hindenburg’s bow the day after the disaster. He holds his Speed Graphic in his left hand, with a Leica slung from around his neck.

Shere took arguably the most famous and oft-reprinted photo of the disaster, the classic shot with the geyser of fire rising above the Hindenburg’s plummeting tail with the mooring mast silhouetted in the foreground. It was the only photo that Shere was able to take of the crash, snapped “from the hip” with his Speed Graphic just as Foo Chu took his first fire photo.

What gave Foo Chu his edge in capturing more images of the crash than professional cameramen like Shere and Becker was the fact that his hand-wound Leica (which photography historian George Gilbert, in a 1987 interview with Dr. Chu, surmised may have been a Leica III, a popular model in the late 1930s) required only a flick of the thumb to advance the film, allowing him to take a shot about every four seconds. In this way, Chu was able to capture a sequence of eight photographs of the Hindenburg’s fall, in addition to his first photograph of the ship hovering over the airfield. As he said in an interview for Photography Magazine in 1952:

"I took the first shot at f/3.5 at 1/10 second, because the light was bad. It was just after a storm. I made the second shot at the same exposure, and then quickly reset the speed dial to 1/100 second for the rest of the pictures. I was too busy shooting to be scared."

Had Chu not had to pause to change his speed settings, he’d very likely have gotten at least one additional snapshot in between his first and second crash photos.

A Leica III 35mm rangefinder camera, which may be the same model (or at least a similar one) to the one that Foo Chu used to snap his Hindenburg photographs.

A Leica III 35mm rangefinder camera, which may be the same model (or at least a similar one) to the one that Foo Chu used to snap his Hindenburg photographs.

When the initial shock of the disaster had faded, Foo Chu realized that his photographs would probably be worth something to one of the newspapers back in New York. He and Benny Kimlau hopped back into the Lincoln and sped away from the air station, heading north to the city. Chu’s interest in selling his photos was not purely mercenary. Not only was he preparing to study medicine at City College of New York, but he also lived with his seven brothers and sisters in a one-room apartment in Chinatown, and they could certainly use the money.

By 11:00 PM, three and a half hours after the disaster, Foo Chu was sitting in the offices of the New York Daily News on 42nd St. The city editor was interested in using some of his photos, and by the time the paper’s late editions came off the presses, their centerfold page contained five of the nine shots that Chu had taken that evening, under the credit line “Amateur photographer Foo Chu.”

However, in the rush to get the photos to press, Chu and the Daily News had not agreed upon payment. Chu met with the paper’s city editor again the next day to discuss compensation for his five Hindenburg photos. The editor initially offered $25 for the whole set of photos, but a classmate of Chu’s helped him to negotiate the final amount up to $25 per photo, for a total of $125. Per the terms of the agreement, the New York Daily News kept the negatives. Not only did the paper run Chu’s photos while the story was still hot, but they also distributed them to other newspapers and publications. Two of Chu’s snapshots (listed here as crash photos #2 and #4) even appeared in the May 15th issue of Newsweek magazine.

It seems, however, that Foo Chu may never have actually received payment for his Hindenburg photos. According to his daughter, family documents indicate that Chu retained a lawyer who attempted to get the Daily News to pay what had been agreed upon, but it is unknown whether or not he was successful.

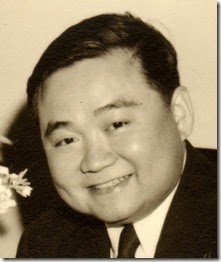

Foo Chu continued with his photography hobby throughout his college years, and a number of his photos were printed in various City College publications. He went on to a long and rewarding medical career, receiving his MD from Cornell University Medical College in 1945 and becoming board certified in pathology and internal medicine. Three years after he graduated from Cornell, while he was in his residency, Chu married Nannie Hainje, who was herself an obstetrician.

Dr. Chu continued to serve the Chinatown community where he had been raised, maintaining a private practice there while also practicing pathology at Lincoln Hospital in the Bronx. Dr. Chu also passed on his knowledge as Clinical Assistant Professor of Pathology at Albert Einstein University Medical College in the Bronx, NY, and as an Instructor in Medicine at Cornell Medical School in New York City.

Well-respected physician that he was, Dr. Chu was often sought out as an expert on health-related issues affecting New York City’s Asian community, in addition to performing a great deal of volunteer work. He served on the Minority Advisory Committee of the New York State Department of Community Health, on the Community Family Council, and also served as chairman of the Chinatown Health Council.

Dr. Chu was also passionate about promoting mental health among the Asian community in New York, and worked extensively with the Hamilton-Madison House, a non-profit settlement house for Chinese immigrants on Manhattan’s Lower East Side. In 1989, Dr. Chu and a group of fellow clinicians co-founded the New York Coalition for Asian-American Mental Health, and Dr. Chu remained an active member of the organization for the rest of his life.

niece (right) during a family trip to Russia in about 2000.

Dr. Foo Chu never retired, continuing to work until he passed away at the age of 81 on February 22nd, 2002 in Tarrytown, NY. He is buried in nearby Sleepy Hollow. Dr. Chu left a substantial donation from his estate to the Hamilton-Madison House and the Coalition for Asian-American Mental Health.

Special thanks to Janice Chu, Dr. Foo Chu’s daughter, for sharing her memories of her father and information about his life, which were of invaluable help to me in expanding his biography to extend beyond his Hindenburg experience. Janice, I’m very glad to be able to put together this short biography of your dad for you to pass along to your children and the rest of your family. Thank you so much!

Thanks too to Jim Fry, who scanned and sent the photo of Dr. Chu shown toward the end of this article.

I must also give credit to two magazine articles that provided me with a great deal of information about Foo Chu’s Hindenburg photos.

The first was entitled How To Make The Front Page by Robert Mann, which appeared in Photography Magazine, February 1952, Vol. 30 No. 2, page 56. Mann’s article featured six of Chu’s nine Hindenburg snapshots as well as a brief write-up about the story behind them, which included the quote from Chu excerpted here.

A second article that I found invaluable was George Gilbert’s “Fifty Years Later: An Amateur’s Leica at the Hindenburg Disaster,” which appeared in a 1987 article in Viewfinder, the newsletter of the Leica Historical Society of America (Vol. 30, No. 4). Not only did Gilbert write an excellent four-page article based on his own interview with Dr. Chu, but he also profusely illustrated it with high-quality prints of six of Chu’s Hindenburg photos.

Oddly enough, however, neither article contained the entire series of nine photographs that Foo Chu shot of the Hindenburg on that fateful evening. I therefore assembled the best versions I had of each photo for this article so that all nine would be represented.