This article and the one that follows may be a slight departure from Projekt LZ 129’s usual focus, but I felt that it was a story that deserved to be shared nonetheless. While it does indeed connect up with the Hindenburg story later on, it is the story of a German airshipman who, like so many of his comrades, flew with the German Naval Airship Division during the First World War, but was then prevented by circumstances from resuming his lighter-than-air career after the war. Though he managed to come close a few times, the opportunities for him to resume flying the giant Zeppelins never quite took hold. Nonetheless, I feel that his tale is certainly of interest to students of airship history, or anyone who just appreciates the uncanny twists and turns of those “cursed to live in interesting times”, as the old saying goes. And thanks to the generosity of his family and the photos and information that they were kind enough to share with me, I’m proud to be able to present, for the first time, an account of the life of Emil Hoff on this, the 122nd anniversary of his birth.

(In Part I, I examine Emil Hoff’s military career, during which he flew with one of Germany’s top airship commanders throughout much of World War I. I have taken the liberty of expanding the scope of the article to include additional information about German Naval Airship Division activities connected to Hoff’s story.)

Emil August Conrad Hoff was born in Altona-Hamburg on July 22, 1893. After attending public school from 1900 through 1908, he took an apprenticeship with a Hamburg grocer. For three years, during which time he worked strictly for room and board, he learned everything there was to know about running a grocery store. The grocer would teach him the various types of coffee and teas, rice, beans, potatoes and so forth, as well as how they were grown and the various ways they could be prepared.

After three years of apprenticeship, which included annual board exams, Hoff left the grocery store and took a position with a ship’s chandler at the Port of Hamburg. He spent the next year provisioning merchant ships, and when he turned 19 in the summer of 1912 he decided that he would enlist in the Navy as a way of fulfilling his mandatory military service. Hoff reported to Kiel for three months of infantry training, after which he was transferred to a signal company. He spent the next three months stationed in Friedrichsort, where he learned Morse code and the use of signal lights and flares. He also studied the fundamentals of navigation. By the end of the year, he had been promoted to the enlisted rank of Signalgast (the equivalent of the US Navy’s signalman) and was serving aboard the Deutschland-class battleship SMS Pommern.

Following three weeks of maneuvers with the I and II Squadrons of the German High Seas Fleet, the Pommern sailed with the rest of II Squadron to Vikö, Norway on its annual summer cruise. However, the ship received a preliminary mobilization order on July 25th, only a few days after they had arrived. II Squadron was ordered to return to Kiel immediately. The crew of the Pommern spent the the rest of that day and night refilling the ship’s coal supply, and the following day they raised anchor and sailed for their home base. Along the way, the Pommern and the rest of II Squadron was shadowed by British warships, however since the two countries were not yet officially at war, the two fleets merely observed one another.

War was declared between the Allies and the Central Powers two days later, on July 28th, 1914. The Pommern, however, did not see major action for nearly five more months. In mid-December of 1914, the High Seas Fleet, under the command of Admiral Friedrich von Ingernohl, provided support for Konteradmiral (Rear Admiral) Franz von Hipper as he took a strike fleet to bombard the northeastern English coast, from Hartlepool to Scarborough. The SMS Pommern and II Squadron were part of von Ingernohl’s forces.

On the evening of December 15th, as the weather on the North Sea began to quickly deteriorate, the signal lights that ran up the Pommern’s mainmast shrouds became entangled and could be neither raised nor lowered. Emil Hoff, who had by this time been promoted to Obersignalgast, had to climb the mast to the short yardarm above the crow’s nest and disentangle the lines. With the wind gusting so badly, Hoff had to keep his feet wrapped tightly around the mast in order to keep from falling. In doing so, he injured his foot.

Immediately following the Hartlepool raid, the Pommern was dispatched to the Baltic Sea to hunt down enemy submarines. The weather was bitterly cold and Hoff’s foot, which had not had time to heal, developed a bone infection which led to blood poisoning. Upon the Pommern’s return to Kiel, Hoff was sent to a hospital in Cuxhaven, where his foot finally received the treatment it needed. Doctors lanced his foot to the bone and inserted rubber tubes to drain off the infection. Emil Hoff remained in hospital for the next six months.

Obersignalgast Hoff took advantage of this long period of recuperation by studying for the examinations for his Signalmaat (signal mate) rating, which would make him a noncommissioned officer roughly equivalent to the US Navy’s petty officer, third class. Another Obersignalgast was also in the hospital with Hoff and this man, who was from the HMS Bremen, was also studying for his Signalmaat rating while he was laid up. In the end, of the ten men who took the examinations, only the two from the hospital, Hoff and the man from the Bremen, passed their exams.

When he was released from the hospital, rather than returning to duty on the SMS Pommern, Emil Hoff was transferred to the 8th Signal Company. This very likely saved his life, as the Pommern would later be blown in half and sunk by a torpedo strike during the Battle of Jutland in the early morning hours of June 1, 1916, with the loss of her entire crew.

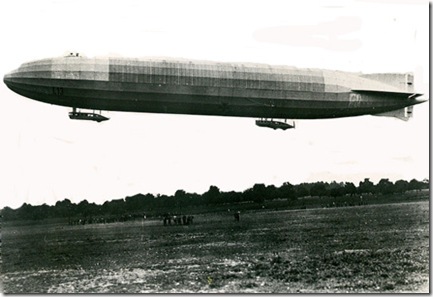

Instead, Hoff would be ordered to the Zeppelin base at Nordholz, where he would join the Imperial Navy’s new Marine-Luftschiff Abteiling (Naval Airship Division). Under the overall command of Fregattenkapitän Peter Strasser, the Naval Airship Division was building up its fleet of airships and needed good men to crew them. Hoff trained to be an elevatorman, and was assigned to a training crew under Kapitänleutnant Gerhold Ratz. After two months of classroom instruction, in the late summer of 1915, Hoff and the rest of his crewmates began to make training flights on the L 14.

One of the most demanding of all airship crew duties, the elevatorman’s job was to control the airship’s pitch and altitude through skillful handling of the elevator wheel, which in turn operated the control surfaces on the ship’s horizontal tail fins. The elevatorman would stand at his wheel facing the port side of the control car so that he could feel the angle of the ship with his entire body. The ability to do this well was the mark of a gifted elevatorman, far moreso than the ability to judge the pitch of the ship via instruments. The elevatorman would also coordinate with the rudderman, who would call out prior to changing the airship’s heading so that the elevators could be applied to prevent the ship from rolling or nosing up or down during the turn.

The sideways-facing elevator control stand on a wartime Zeppelin, L59.

The sideways-facing elevator control stand on a wartime Zeppelin, L59. Note the altitude navigation instruments.

During training flights, the L 14 would carry two apprentice elevatormen. One would man the elevator wheel while the ship ascended, and the other would control the wheel while the ship landed. On one of his first flights, Emil Hoff was assigned to takeoff duty, which meant he was to man the elevator wheel during takeoff, climb to approximately 2,000 meters, and then level the ship off. Standing directly behind him was the L 14’s commander, Kapitänleutnant Alois Böcker and Dr. Hugo Eckener, the Naval Airship Division’s director of airship crew training and senior advisor to Fregattenkapitän Strasser.

As one of Germany’s top Zeppelin pilots and a confidant of Count Ferdinand von Zeppelin himself, Dr. Eckener was considered one of the foremost authorities on what made a good airshipman. For Emil Hoff, the prospect of having his ship handling scrutinized so closely by Dr. Eckener and Kapitänleutnant Böcker was rather sobering. As he would later recall, “I was really scared to have such big shots breathing down my neck.”

But evidently Hoff didn’t do too badly, especially given his lack of experience as an elevatorman. His training continued apace and over the next year at Nordholz, Hoff not only gained experience at the elevator wheel, but he was also trained as a rigger. The riggers were another vital part of the crew, as they maintained the airship’s gas cells, the interior bags that held the airship’s lifting gas. Hoff was taught how to gauge the fullness of each cell by feel and by the way they hung in their individual bays. In this way, he could tell how much lift each gas cell would provide, how much additional gas would be needed to top them off and so forth. Prior to every flight, he would make a full inspection of all cells and provide the ship’s commander with a written report.

In addition, he was responsible for filling the cells with hydrogen and of determining the purity of the hydrogen in each cell. This was important, because maintaining a high level of gas purity was vital to the safe operation of a hydrogen airship. The Germans took no chances with this, and maintained purity levels of 95% or higher. Lower purity meant that a higher percentage of oxygen was mixed in with the hydrogen, thus making it more easily combustible and potentially even explosive. Hoff was also charged with valving gas from the gas cells during flight as required and ensuring that the valves were closed and dry when not in use. Wet gas valves could sometimes freeze open at high altitudes, and the ship would lose valuable lift as its hydrogen uncontrollably vented.

The training flights continued throughout 1916, once or often even twice a day. These flights would last between an hour and a half to two hours, generally at altitudes of 2,000 feet or less. Hoff’s proficiency at his flight duties increased, and then in the summer of 1916 he went to Cuxhaven to receive machine gun training along with a group of others – among them Obersignalgast Adolf Fuchs, who would go on to serve as an elevatorman on the L 57 and the L 59 under Kapitänleutnant Ludwig Bockholt. All Zeppelin crew members needed to be able to man the ship’s mounted machine guns to ward off enemy aircraft, which had begun to use incendiary ammunition – deadly to the hydrogen-filled German airships. Hoff and his comrades received standard military instruction in how to fire and maintain the airship’s machine guns.

In March of 1917, Emil Hoff was selected by Kapitänleutnant Martin Dietrich to join the crew of his new command, L 42. In late December of 1916, Dietrich had been in command of the L 38 and was flying from the airship base at Alhorn to the Russian front, where he was to bomb Reval. The ship was forced down near Libau by a winter storm, completely covered with heavy ice and with gas cells pierced by ice chunks being thrown by the propellers.

and the shuttered bomb bays can be seen along her lower keel.

Though the wreck was purely due to the inclement weather, the ship’s elevatorman, Signalmaat Hellbach, blamed himself for the crash to such an extent that he suffered a nervous breakdown. When Dietrich was given command of the L 42 in February of 1917, he needed to find himself a new elevatorman.

Kapitänleutnant Dietrich contacted the training division and requested the best elevatorman they had. Emil Hoff, having maintained an impeccable training record, was personally recommended by both Kapitänleutnant Ratz and Dr. Eckener himself. Dietrich selected Hoff as his new elevatorman, and he joined the crew of the L 42 on March 16, 1917, with a bombing raid on England scheduled for that night. (Coincidentally, Dietrich, commanding the L 22 at the Battle of Jutland, had witnessed the destruction of Hoff’s old ship, the Pommern.) Hoff, experiencing a true “trial by fire,” would later remember very little about that first flight under Kapitänleutnant Dietrich. Not only was he flying directly into England’s coastal defenses, but Fregattenkapitän Peter Strasser, the Führer der Luftschiffe for the Naval Airship Division, was aboard as an observer. “I did not know what was what,” he would recall. “You have no idea what I was feeling.”

But the raid that night was successful, and Hoff soon became a seasoned member of the crew. Friendships naturally developed, and one of the men with whom Hoff became close was Obermaschinistenmaat Karl Nordmann. Nordmann’s main duty was to assist the sailmaker in maintaining the ship’s gas cells and valves, much as Hoff had done during his training and would continue to do during his service aboard the L 42.

Nordmann was also proficient in the operation and maintenance of the Maybach engines that propelled the ship, and would assist the engine crews in the event of serious breakdowns. Each engine was tended by two mechanics, who had been specially trained on the ship’s high-altitude motors at the Maybach Motorenbau in Stuttgart. Hoff would later remember many of these men: Maschinistenmaate Ernst Weiss and Carl Lauterbach, Obermaschinsten Messer, and Maschinisten Hayn, to whom the engine crews reported.

In addition to manning the elevator wheel, Hoff was also tasked with doling out rations of Cognac to the crew. The L 42 was one of the Naval Airship Division’s “height climbers”, designed to fly above the range of enemy anti-aircraft fire and fighter planes. When the L 42 would climb above 1,500 meters (4,000 feet) the temperature would drop precipitously due to the high altitude, and the commander would order that each man be given a shot of Cognac to ward off the cold – one shot per man, per flight. Since some of the members of the L 42’s crew did not drink, Hoff would sometimes give some of his closer friends an extra shot.

There was the usual scuttlebutt that filtered its way through the ranks. In the summer of 1917, Hoff heard a particularly interesting story. Plans were then underway to send the L 57 to Africa to resupply Generalmajor Paul Emil von Lettow-Vorbeck’s troops, who were the last holdouts against the British in German East Africa. The idea was for the Zeppelin to be flown from the Germans’ southern-most airship base, at Jamboli in Bulgaria, to Lettow-Vorbeck’s location in Mahenge in Tanzania. There, the Zeppelin would offload its cargo of arms and supplies and then itself be cannibalized and its parts used to make everything from boots and tents to a radio station. As it was to have been a one-way flight, the crew would then join Lettow-Vorbeck’s forces as infantrymen.

As the story has always been told, even in Dr. Douglas Robinson’s painstakingly researched and highly regarded reference volume, The Zeppelin In Combat, command of the L 57 and its Africa mission was given to Kapitänleutnant Ludwig Bockholt due to his having been a relatively junior officer. Since the ship’s commander would join the crew as part of Lettow-Vorbeck’s infantry, likely for the remainder of the war, Naval Airship Service command did not want to lose one of their more seasoned airship commanders.

However, quite a different story was relayed to Emil Hoff by one of the mess stewards at Nordholz. The way it was told to Hoff, Kapitänleutnant Dietrich and Kapitänleutnant Bockholt had been in the base officers’ casino where, in the presence of Fregattenkapitän Strasser, they had gotten into a particularly heated argument over which of them would command the L 57 on its Africa flight. As Hoff would later recall, “They drew matchsticks and Bockholt won. Just think, if Dietrich had won I’d have gone to Africa!”

Wreckage of L 57 at Jüterbog, October 8, 1917

In the end, the Africa mission fell short of its goal. In September of 1917, L 57 was wrecked in a ground handling accident. Bockholt was assigned the L 59 as a replacement, and the mission was delayed until late November. When L 59 was a little more than halfway to its destination, Bockholt received a recall order from Berlin, based on erroneous intelligence that indicated that Lettow-Vorbeck had been overrun. L 59 returned to her base in Jamboli.

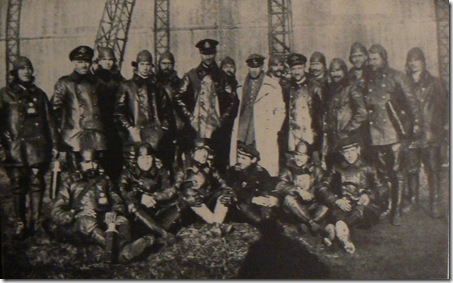

Crew of L 59 after returning from the Africa flight

Meanwhile, L 42 continued to fly missions, and by this time the Allied fighter planes were becoming an ever greater threat. Emil Hoff’s comrade, Obermaschinistenmaat Nordmann, designed and built a special machine gun platform for the L 42 to be suspended from one of the ship’s main rings just astern of the aft engine gondola. With a sheet metal windscreen to protect the gunner against the engine’s prop blast the platform, which was generally manned by Bootsmannsmaat Martin Bishoff, would serve as additional defense against enemy planes.

The dangers aboard a Zeppelin did not come strictly from enemy attacks, however. During one flight, Emil Hoff was conducting an inspection of the L 42’s gas cells and had to pass Nordmann on the narrow keel gangway. Nordmann was on the telephone to the control car, and Hoff tried to swing himself past. Hoff’s foot slipped and he began to fall toward the ship’s cotton outer covering below. He was caught by some rigging wires and Nordmann grabbed him and pulled him back up onto the gangway.

Hoff was dazed by his near miss. “My heart was spinning. I could picture myself falling through the ship’s envelope.” Nordmann gave Hoff oxygen from the ship’s Dräger oxygen apparatus, and within a few minutes Hoff’s head had cleared and he was able to resume his gas cell inspection.

On another flight, a raid over England on the night of May 23-24, 1917, the L 42 encountered severe weather and Kapitänleutnant Dietrich had no choice but to order the ship to proceed through the storm. Suddenly, the entire ship was lit up by a bright blue flash as a bolt of lightning struck the ship, exiting through the aft portside propeller. The weather continued to buffet the ship, which was struck by two more bolts of lightning before her mission concluded and she arrived back at her base at Nordholz the following morning. The aft port propeller through which the first lightning bolt had left the ship was removed and later cut into small, highly polished pieces which were distributed among the crew as mementos of their having survived a direct lightning strike on their airship.

The bombing raids themselves were a testament to the training and skill of the L 42’s crew. As the Zeppelin neared its target, Kapitänleutnant Dietrich would determine the target area as well as the altitude at which the ship would make its approach. Their position was marked and maintained by Steuermann Guteseit, the ship’s navigator, and Leutnant zur See Eisenbeck, the Executive Officer, would serve as bombardier, watching the approach to target through the ship’s bomb sight and checking the wind direction. He would provide the rudder man, Bootsmannsmaat Jarowchinski, with specific directions to their target, and each time he turned to port or starboard Jarowchinski would call out the direction to Emil Hoff, who would compensate for the turn on the elevator wheel to keep the ship level. Finally, the ship’s bombs having been dropped, Steuermann Guteseit would calculate the optimal course back to base.

Once they had made it back to base, Hoff would bring the ship in for landing. By now he had become quite a steady hand at the elevator wheel. He would later recall:

“One of the little tricks I used when coming in for a landing was to always keep the tail just a little low. I kept two ballast bags full in the back, just enough to keep it a little bit heavy there, so that the tail would hit the ground first, not the gondolas. Kapitänleutnant Dietrich would give the orders for landing and Leutnant zur See Eisenbeck would notice the tail heaviness on the vernier scale. Dietrich didn’t know the tail was heavy and he would chase Eisenbeck away from me – he told him to leave me alone and let me land the ship.”

It turned out, however, that as high profile as the bombing missions were, the L 42 actually spent most of its time serving in a capacity to which Zeppelins were infinitely more suited – aerial reconnaissance.

“Altogether, I made five flights to England. However, we made many scouting flights over the North Sea. On these reconnaissance flights we carried a crew of 24 men, while on the England flights we only had 21 men. This was to save weight and allow us to attain greater height. On one occasion, in late 1917 or early 1918, we were out scouting over the North Sea for six weeks. That is, we had three ships out on watch, three ships sleeping and three ships on the way as relief. We stayed out for about 12 hours every day for six weeks, looking for the British fleet. This was during the time we thought they were coming and we were constantly watching for them.”

One bombing raid that Hoff remembered particularly vividly took place on March 13, 1918. A flight of five Zeppelins, led by Führer der Luftschiffe Strasser, had made a raid on England the night before on March 12, with limited success. Strasser ordered another raid, and the following morning the L 42 took off from her base at Nordholz, joining up over the North Sea with L 52 and L 56 out of Wittmundhaven.

“We got our orders to go to England. We left the shed at Nordholz at about 11:00 in the morning and went right up. The weather was very nice and visibility was good. Late in the afternoon, as we approached the coast down near the London area, we met British cruisers and torpedo boats. We were at about 5,000 feet, fairly low, when all of a sudden we saw them shooting at us. Kapitänleutnant Dietrich yelled, “Hoff! Up!! Up!!” But I couldn’t go up just like that. I had to get away first. So, we slipped away and slowly rose while they continued to shoot at us. We finally got free of them in about 3,000 – 4,000 more feet. Then we came upon the British coast.”

“We soon came upon a lumber ship, Danish or Swedish or something, and we tried to bomb it – but we missed. As it started to get dark, we crossed the coast at Flamborough Head at about 6,000 feet and then proceeded to cross over Middlesex and the Midlands. At this point we were ordered back – all ships to return. But the L 42 was already over England and we had excellent weather conditions, very cloudy but with good moonlight. Dietrich and Eisenbeck decided to attack Hartlepool.”

Kapitänleutnant Dietrich would later be very frank about the fact that he had chosen to disobey what amounted to a direct order when the ship received Strasser’s radio message, “To L 42. Revolving shed. Führer der Luftschiffe.” Dietrich would later explain, “We had seen two convoys and were maneuvering to attack the second one when the recall came in. We thought we could bomb them before Starting back to Nordholz, but then the English coast came into sight. It was too much! It had been a year and a half since we had had a chance to raid England, and now, with the island in plain sight, we were being ordered to go home without attacking. ‘We’ll keep going,’ I said to my executive officer. But I knew it had to be a success. If I failed, I would have to quit the service.”

So, Dietrich kept the L 42 off the coast for the next 40 minutes or so, waiting for darkness to fall. As it did, the crew could see the English coastal towns lit up brightly – clearly, nobody there was expecting a Zeppelin raid. Once Dietrich ordered the L 42 toward Hartlepool, at 10:05 PM, the British anti-aircraft defenses opened up on them. Hoff once again tried to make the L 42 as difficult a target as possible.

A Zeppelin caught in searchlights during a raid over England.

“We were fired on for over an hour by anti-aircraft guns. Their shots went over us, under us, beside us. Jarowchinski kept yelling, “I turn port!” and “I turn starboard!” as we took evasive action to avoid the shells. We finally dropped our bombs on Hartlepool from about 6,000 meters (19,700 feet) and then Jarowchinski followed the course back toward Ahlhorn.”

In the space of about ten minutes, the L 42 had dropped twenty-one bombs on West Hartlepool, destroying a number of buildings and doing £14,280 worth of damage. Eight people on the ground were killed in the raid, and 29 others were injured.

“On the return, we ran into very bad weather. We dropped down to about 1,000 meters (3,300 feet) but the wind made it very rough. We came near to what we thought was Borkum and dropped down very low, to about 300 meters. Borkum has a little railroad which we saw and then we knew for sure exactly where we were. The old man gave the order, “Antenna out!” so that we could listen to what was going on. The radio man, Funkentelegraphist Heinrich Wilkan, soon heard the L 52 reporting in and asking permission to land at Wittmundhaven. Not long after that, he heard the L 56 also asking permission to land, They’d spent the whole night out in the bad weather over the North Sea while we’d flown back from Hartlepool! So, the L 42 also reported in and asked permission to land at Nordholz. We saw the three sheds at about 9:30 in the morning, but the weather was still very bad. We couldn’t enter our own shed due to a cross wind, so we were ordered to the revolving shed.”

A trio of Zeppelins returning to base after a bombing raid over England, circa 1917.

“We came into Nordholz, dropped over the fence, and settled down on the field just like a lame duck. Then the ground crew pulled us into the revolving shed. That night, as tired as we were, Bischoff, Wilkan and I quickly finished our duties and then went off to the little town of Lüdingworth together for a little relaxation.”

Dietrich, despite the success of his Hartlepool raid, fully expected to be disciplined for disobeying the order to return to base. “Strasser was a stickler for regulations,” he would later say, “and I wondered what kind of trouble I’d be in. When I saw he was not out on the field [when the L 42 landed] according to his usual custom, I prepared for the worst.”

In the end, Fregattenkapitän Strasser listened coolly to Dietrich’s verbal report on the raid, then slowly smiled and said, “In honor of your successful attack, I name you Graf von Hartlepool (Count of Hartlepool).” Dietrich’s disobeying of orders was not mentioned in Strasser’s report, and in fact the Hartlepool raid was noted in Dietrich’s service record by the Kaiser himself as “Very gratifying!”

By the summer of 1918, however, the war was already as good as lost for Germany. In early June, the L 42 was reassigned as a training ship, and Dietrich and his crew, including Emil Hoff, were temporarily without an airship. It may have been just as well for them.

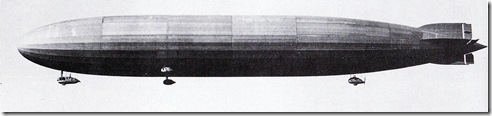

On August 5, 1918, despite the war being all but over, Führer der Luftschiffe Strasser ordered a group of five Zeppelins on a bombing mission against London. The raid would be conducted by L 53, L 56, L 63, L 65, and the brand new L 70 with Strasser himself aboard. That evening, as the airships approached the English coast, L 70 was met by a trio of British planes and shot down. Strasser and the entire crew died as the L 70 fell in flames off the coast of Norfolk. Six days later, L 53, under the command of Korvettenkapitän Eduard Prölss, was shot down by a ship-based Sopwith Camel off the coast of Terschelling, again with the loss of all hands. This effectively ended the Naval Airship Division’s active role in the war.

Führer der Luftschiffe Peter Strasser Korvettenkapitän Eduard Prölss

The day before Prölss and L 53 were shot down, Kapitänleutnant Dietrich and his crew were assigned to another of the latest airships to come out of the Luftschiffbau at Friedrichshafen – the L 71. However, with the Naval Airship Division having been all but withdrawn from action, the L 71’s service was limited primarily to practice flights. Emil Hoff remembered one of these flights.

“One time we had the L 71 out on a practice flight and were coming in to make a landing. We were over the hangar and very low, about to make a landing, when the wind came up and suddenly slid us sideways. Dietrich tried to grab the controls and raise the ship – which would, of course, force the tail down onto the hangar. I hit his hands away and he didn’t say a word. Then we slid just over the hangar. Dietrich looked around, but said nothing. It was not his business at all. Had he raised the ship, the tail would have surely gone down and crashed into the hangar. I knew he wasn’t mad, as afterward he thanked me for the fine way that I had handled the ship.”

When the war ended a few months later, Emil Hoff was discharged from the German Navy and returned home to Hamburg. The Navy’s remaining Zeppelins would be awarded to the Allied nations as part of the war reparations for which Germany was liable under the terms of the Treaty of Versailles. L 71, now hung up and deflated at Ahlhorn, was given to England along with L 64. Both airships would later be scrapped by the British due to limited hangar space. The old L 42, also scheduled to be handed over to the Allies, never made it. On June 23, 1919, the Zeppelin crews at Nordholz and Wittmundhaven entered the hangars where their airships had been deflated and hung from the rafters awaiting the final division of the spoils of war among the Allies. The crewmen pulled away the supports beneath their ships and loosened the suspension tackles, allowing the fragile structures to fall to the hangar floor. Absent their lifting gas, the fall of but a few feet was enough to break the Zeppelins’ keels and crush their framework beyond repair. L 42 met her fate alongside the L 63 in the Nordholz “Nogat” hangar.

I would like to thank Emil Hoff’s daughter, Louise Robertson, and his grandson, Raymond Robinson, for providing me with the material on which I was able to base my research into Hoff’s life, both as an airshipman in Germany during WWI and as a representative of Tidewater/Veedol Oil here in the United States during the post-war years.

One of the most valuable sources of information for this first part of Emil Hoff’s story was a piece called “The Story of a Zeppelin Elevatorman”, written by Richard Duiven and Ed Folz, and based on interviews that they had conducted with Hoff about his experiences flying for the German Naval Airship Division in the First World War. I could not have gone into nearly the depth of personal details about Hoff’s time as an airshipman that I was able to without the time and effort that Duiven and Folz put into gathering Hoff’s recollections.

Additional information about German Naval Airship Division actions in WWI, as well as many of the accompanying photos. were drawn largely from THE ZEPPELIN IN COMBAT, by Dr. Douglas Robinson.

Philipp Lenz, center, examines injuries to his hand as he and other survivors arrive at the dispensary.

Philipp Lenz, center, examines injuries to his hand as he and other survivors arrive at the dispensary.